0. On Image Synthesis

As discussed in the Workshop about “Synthesizer”, the synthesis principle of synthesizers is based on the sum of frequencies. I aim to bring this principle into the realm of visual images rather than audio. Before proceeding, let’s address a few conditions.

1. Fundamental Elements of Images

While the basic element of audio synthesis can be simply defined as a sine wave, no such foundational element readily comes to mind in the world of images. How should we find it?1

Let’s acknowledge that dealing with images is more complex than dealing with sound. Unlike sound, which consists solely of one-dimensional waves, an image is a two-dimensional spatial concept with x and y axes. Therefore, the frequency of visual information becomes more complex in its directionality. Furthermore, the eye’s resolution is far higher than that of the ear. In other words, it has higher resolution. These two facts mean that the amount of information we must interpret—or convey—from visual images is greater than that from sound.

The purpose of this practice is not to clearly define every attribute of an image. That is far too vast a subject. It suffices to speculate within limited scope on how image synthesis might function. For example, no synthesizer in the world strictly adheres to the fundamental principle that all sounds can be produced solely through the synthesis of sine waves. This is because it is nearly impossible to prepare the countless oscillators needed to fully capture the world’s complexity. Therefore, this practice aims to adopt one approach to image synthesis and explore its potential.

2. Image Attributes

First, let us categorize image attributes into three types.2

- Color

- Form

- Texture

Among these, color is relatively distinct from the other attributes, but the remaining two are not. If form refers to specific shapes or boundaries within an image, texture could be defined as patterns or variations in density within specific areas of the image. While these definitions are fairly clear within the realm of human intuition, they are challenging to translate into precise mechanical criteria. Consequently, in the process of applying the principles of JPEG compression used in this practice, texture and form will be defined somewhat indistinctly. We will exclude discussions on color and limit our scope to the synthesis of shape alone—combining form and texture under this term.

3. JPEG Compression and DCT

The JPEG compression method (hereafter JPG) is the most widely used standard among lossy compression techniques for reducing the file size of digital images.3 Simply put, JPG reduces storage capacity by treating information poorly recognized by the human eye as unimportant—blurring or deleting it—a process known as lossy compression. In this process, JPG divides image information into two major categories for processing: color and shape.

JPG processes color by separating it into luminance (brightness) and chrominance (color) information. Brightness information is considered more important than color information because the human eye is more sensitive to changes in brightness. Consequently, JPG reduces storage space by sacrificing (subsampling) color information. Compressed digital images lose some actual color information, but this difference is difficult to discern clearly with the naked eye. Consequently, JPG becomes an efficient compression method that defends against visual quality degradation of the original image while reducing actual data.

The process by which JPG handles shape is more complex. First, JPG divides the entire image into 8×8 pixel blocks for processing. Each block is then compressed independently. (The blocky appearance in digital images, often called JPEG artifacts, arises during this process.) During compression, these 8×8 pixel blocks are converted into a combination of 64 basic patterns using a method called the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT). This converts spatial domain information into frequency domain information, which is also related to the hierarchy of information discernible by the human eye. We perceive low-frequency components, which form the large structures of an image, well, but we do not perceive high-frequency components, which are detailed and have complex shape changes, as well. Therefore, JPG increases compression efficiency by sacrificing the high-frequency components in the transformed 8×8 pixel frequency domain.

4. Discrete Cosine Transform

JPG’s DCT follows these steps:

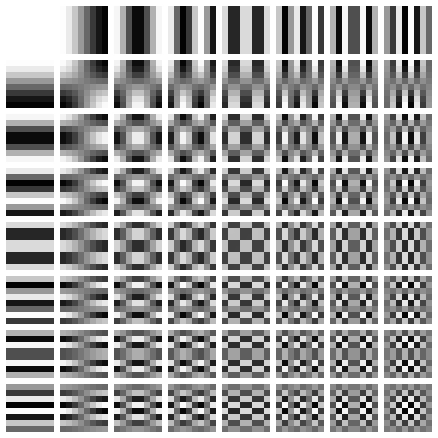

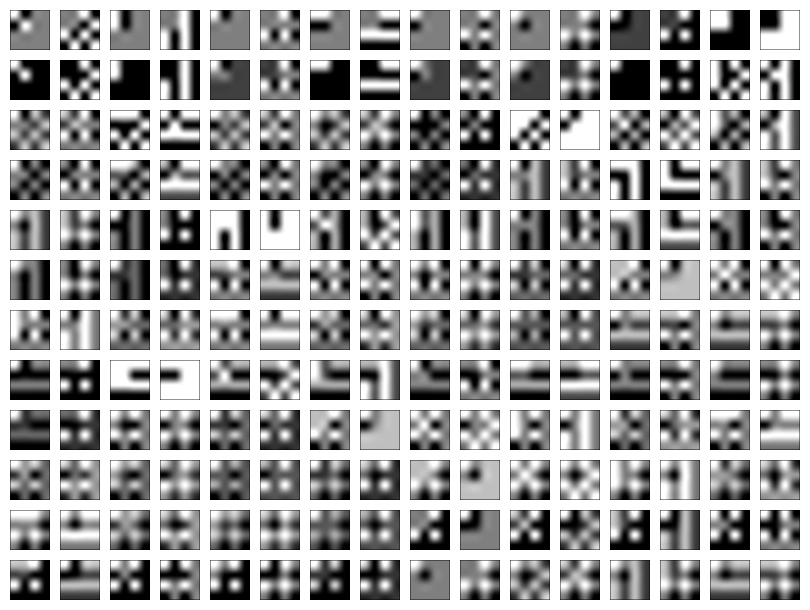

- An 8×8 pixel block has 64 basic patterns (DCT coefficients). 4

- The original image is divided into 8×8 pixel blocks, and the information from each block is read.

- The block’s information is converted into 64 weighted coefficients for the patterns via DCT.

- The 64 patterns are combined according to these weights to reconstruct the block’s image.

- The compression ratio varies depending on how much high-frequency information is sacrificed.

5. Image Generation Using DCT (DCT Resynthesis)

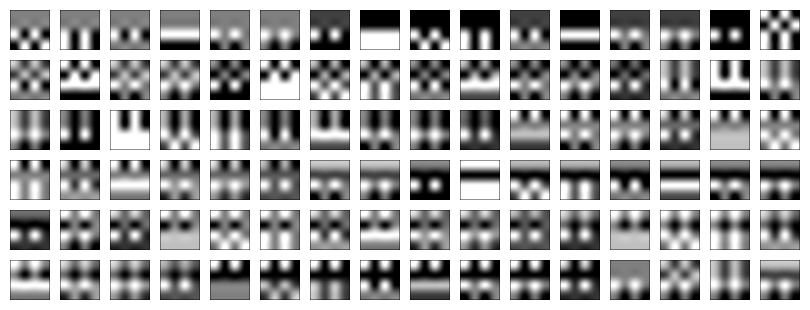

If DCT compresses images, it should also be possible to reverse this process to generate images. This practice originated from this idea.5

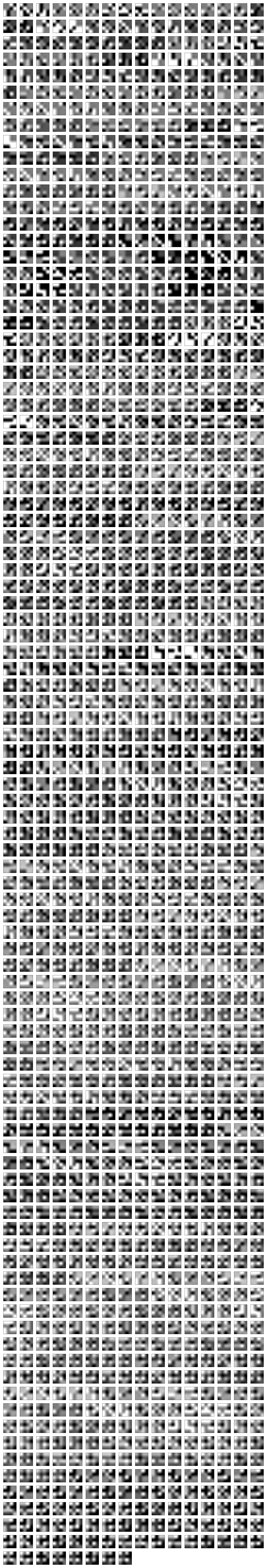

As previously noted, the Discrete Cosine Transform yields 64 DCT coefficients. The ultimate goal is to combine these to obtain a shape image, but an 8×8 grid presents too many possibilities for experimentation. Therefore, we decided to control the variables for the experiment. The experimental conditions are as follows. 6

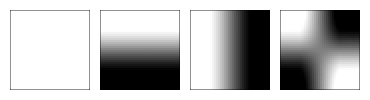

- The format of the generated shape image is set to 4×4 pixels.

- The generated shape image is composed of a combination of four 2×2 pixel blocks.

- Consequently, each 2×2 pixel block possesses one of four basic patterns (DCT coefficients).

- By limiting weights to 0 and 1, generate all possible images within these constraints.

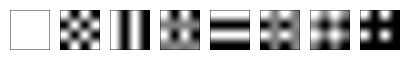

Accordingly, I obtained 4 basic patterns and 1,808 shape images. These represent all possible images under the experimental conditions.

The number of ways to combine 2×2 DCT coefficients to create a 4×4 image can be summarized as follows:

A: An image filled entirely with the same basic 2×2 pattern

B: Image filled with two different patterns, each occupying half the space

C: Image filled with one pattern occupying 3 cells and another pattern occupying 1 cell

D: Image filled with one pattern occupying 2 cells, another pattern occupying 1 cell, and yet another pattern occupying 1 cell7

6. Practice Postscript

Through this series of processes, I sought to demonstrate that concrete images can be generated through the synthesis of abstract fundamental elements. However, the shape images produced as a result of this practice still have the limitation of not significantly departing from abstraction. Nevertheless, I am confident that these images exemplify the DCT principle as a potential methodology for image synthesis. In subsequent practices, I will further develop this methodology to obtain more concrete and useful form images. Moreover, the form images generated in this way can be connected to various contexts. For example, how do form images generated as the sum of frequencies through a specific methodology differ from AI-generated images using the Stable Diffusion method? Can Stable Diffusion, which is also based on learned data, be considered a form of “synthesis”? These questions clearly remind us of the potential inherent in potential images.

-

In this text, “image” is limited to mean two-dimensional flat images. ↩

-

The three attributes of an image follow the viewpoint of Professor Jae-Hyouk Sung from the Department of Visual Communication Design, College of Design, Kookmin University. ↩

-

Video explaining JPG, helpful for this practice: youtu.be/Kv1Hiv3ox8I?si=iVc1zerfmSAGd9qW ↩

-

The 64 DCT patterns are composed of combinations of horizontal and vertical frequencies. This is because JPG handles two-dimensional planar images, requiring both horizontal and vertical axes. Furthermore, since an 8×8 pixel grid can yield 8 types of horizontal and 8 types of vertical frequencies, the total number of possible combinations results in 64 patterns. ↩

-

Strictly speaking, the inverse process of JPG compression does not fully hold. Digital image compression methods are broadly divided into lossy compression and lossless compression. JPG is a prime example of the former, while PNG and GIF are representative examples of the latter. (Typically, anyone who has worked with digital images knows or feels intuitively that the former format is lighter than the latter.) That is, JPG does not retain the original information from before compression in its entirety.

However, this loss occurs only during the quantization process of JPG; the DCT itself can be perfectly reversed. To restore a JPG-compressed image to its original state, the inverse discrete cosine transform (IDCT) process must be applied, which does not introduce loss. This is because DCT is a transform method based on the Fourier transform. Based on this reasoning, I concluded that the principles of DCT are well-suited for application in image resizing. ↩ -

All image generation tasks were produced using Python scripts. Images were generated by assigning each frequency weight either 1 or 0, and the resulting 4×4 pixel images were enlarged to 40×40 pixels for easier viewing. All shape images attached to this article are upscaled to 40×40 pixels. ↩

-

The number of cases where every cell is filled with a different pattern is excluded. This alone would form 43,680 distinct images, an excessively large number relative to their structural significance, so they were excluded for now. The images from A to D alone should suffice to explore the principles of image synthesis. ↩